Smartphones are, by their nature, iterative products. But if you've felt that this iteration has started to slow a bit in the last few years, you're not alone - and you're probably not wrong, either.

Think about it: smartphones have a pretty set list of characteristics and features we evaluate in order to judge the overall quality of a device. Some are more subjective than others - design, for example - but many are also quite objective, even if quite difficult to measure objectively sometimes. How fast is the phone? How long does the battery last? How good is the camera [at night, for video, in slow motion, etc.]? Is it durable or ruggedized? Does it break easily? How big is it? How good is the display?

And among those criteria, some things are basically starting to be taken for granted, especially at the high end of the market. 2K display? OK, sure, that's just about a given on any phone over $500 these days not made by Apple. LTE? Practically a requirement. High-resolution camera that is basically within shouting distance of most other high-end cameras? Yep. Battery life that isn't actually, legitimately terrible [comparatively]? Sure, what else have you got?

And not all of these things were always givens, lest we forget. The HTC ThunderBolt (I'm never sure on the camel-casing there) had battery life that really would struggle to get most people through a day, or even half a day. Some phones were so slow that they were borderline-unusable in certain conditions - can you imagine going back to a G1? Hell, or even a DROID Charge. But even so, those devices were outliers in those ways and were still otherwise pretty much like the phones we use today, just worse. Things have, obviously, improved. Some things we pretty much objectively have right at this point, though - smartphones are remarkably good products, generally speaking, and that would have been a fair bit harder to say five or six years ago.

And over the course of six years here at Android Police, much of what I have seen change in Android smartphones big-picture-wise comes down to one of two things.

- A basic technological advancement that improves the quality of a normal, necessary part of a smartphone, and generally trickles down to every manufacturer in the industry over time

- Something Google does in Android that makes using a smartphone better (depending on who you ask, of course) in some way

Go back to my review of the DROID Charge - a phone I rather thoroughly disliked, mostly because it was in the heyday of TouchWiz being a legitimately poor user experience that had the industry-leading bonus of also negatively impacting device performance. That review was published, give or take, five years ago. Here's a picture the Charge's camera took.

Are you physically repulsed? I'm guessing there are some mid-range devices with roughly similar daylight capture performance on the market out there right now. You can nitpick that photo, sure - there's a fair bit of sky noise and even five years ago I'd still say Samsung's sharpening is on the aggressive side - but it's basically fine. If your significant other asked you, "hey, do you have that photo from the beach five years ago?" they're not going to look at that and say, "Oh, what a dumpster fire of a picture, guess we'll just trash it - no point in using that!" (Unless they're a professional photographer and/or a huge asshole.)

Now, there are more marked performance improvements in areas like video quality, low-light captures, capture speed, and control of the camera itself. And those are valid points - if smartphones hadn't really improved all that much in the last five years in basically any way, we'd all probably have just stopped buying new ones. But the changes are still iterative. You could still take video on a smartphone five years ago - HD video, even. You could still use the flash to take a picture in the dark. Some phones even had burst photo modes. Not to mention you could share those photos near-instantly to the internet. I mean, we're talking about some features that dedicated point-and-shoots didn't necessarily have (hey, very few still have that last one). Think about that. Five years ago.

Pictured: an older, smaller, uglier, worse version of the phone you have today. Basically.

A smartphone five years ago had two cameras, a screen, always-on mobile data, a lithium-ion battery that never lasted quite as long as we wanted to but got the job done, made phone calls, browsed the web, was a portable GPS / navigation device, and had apps. What does a smartphone today do that is fundamentally different? There may be a few small things here and there - NFC tap and pay, for example - but you're going to have to look hard to see a real shift in the smartphone paradigm in that time.

I'm sorry, I know, you came here because Nexus. And I'm getting there. The point I'm making is this: have smartphones gotten better in the last five or six years? Certainly. Sometimes in very noticeable ways. Are smartphones fundamentally different today than they were five or six years ago? No. They are remarkably similar.

And in the past two or so years, I think even the "noticeable improvement" side of the equation has begun to slow. Cameras? We've got 4K video, slow-motion, more usable low-light performance, and refined auto-focus. Those are the big ones I'd identify, because in normal-everyday-use, smartphone cameras haven't really gotten insanely better. Just in a few rather specific areas. Screens? Super AMOLED is about the pinnacle of what we've achieved, but again, in two years, the improvements there are marginal. Performance? Phones are faster, yes, but the change is much less noticeable, I'd argue, than in previous years. Battery life? I'm not even sure it has actually improved.

Xiaomi's Mi 5 is a case in point for smartphone commoditization, offering huge specifications for relatively little money.

You may have heard the word commoditization thrown around a lot in regard to smartphones recently. And what you've heard, I'd argue, is probably right: smartphones are becoming more same-y than ever, and it's becoming a race to the bottom - whoever can cram the best parts in the best plastic/glass/metal internet-camera-box for the lowest price wins. At least, that's a very broad way of looking at it, and ignoring special cases in the market like Samsung and Apple who have substantial brand clout they can successfully fold into the MSRP of their respective products. But almost everyone else in the business is having a very hard time balancing the differentiation, cost, and profitability equation effectively enough to remain competitive without either pricing themselves out of the market or becoming too similar to competitors they can't outprice.

But what does this have to do with the Nexus program?

Let's shift directions, before I bore you to death with commoditization. I want to start with a premise: I believe the Nexus program has two key advantages over phonemakers like LG, Sony, Xiaomi, Motorola, or Huawei, and that now more than ever it can be poised to exploit those advantages.

The first is that the Nexus program does not have to actually make money - especially in the short term. It doesn't even have to break even. Google reaps massive profits from its core business - ads via search - that are in no way dependent upon or beholden to what Google does with Nexus. Nexus phones sell great? Search profits probably improve. Nexus phones sell terribly? Search profits are totally unaffected. Contrast this to, say, Xiaomi. Xiaomi's core business model requires that they sell a metric butt-ton of smartphones. If they can't sell enough smartphones, their core business is threatened. Other businesses are less at risk, looking at companies like LG and Huawei, but at the end of the day, both of those companies profit on the basis of selling a product. Having a product that loses money is bad for business, because the entire point of your business is to make money selling people things. Sure, there are considerations like building brand loyalty, ecosystem, and awareness - but those are entirely secondary.

The second is that Google can do whatever it wants to Android and its own Google services. And as far as I'm concerned, Android and Google services are the bulk of the innovation engine pushing Android smartphones forward in meaningful ways at this point, and that proportion will only increase in the next few years. As smartphones rubber-band ever-closer to an optimal set of features, specifications, and performance at a given price point, Android itself begins to take an outsized role in what can make one phone different from another. But Google can do something no other manufacturer can - at least not without losing access to the Play Store - it can change core features of the operating system, because Google (duh) defines what constitutes Android pretty much everywhere except China and Amazon.

And this gives the Nexus program power. A special power that no other Android phone manufacturer has - one that Google has started to assert more authoritatively in recent years. Let's take a quick trip down Nexus memory lane and see how that strategy has evolved.

Nexus: A Brief History

This is the only surviving photo of my Nexus One, which I very much loved. I MISS YOU LIGHT-UP TRACKBALL

The first few Nexus phones were undisguised developer reference devices - the Nexus One, Nexus S, and Galaxy Nexus all courted the possibility that regular people might want a "Google Phone," but they were pretty clearly positioned more for enthusiasts and developers. The Nexus 4, though - that was an identifiable moment of change, I think we can all agree. It was cheap, you could buy it direct from Google [in theory], it was well-equipped, it looked distinct, and Google almost kind of sort of marketed it a little bit, I guess. Google's toes were clearly in the water with the Nexus 4, and with the Nexus 5, they decided to dip them a little deeper - it worked. The Nexus 5 was probably the best-selling Nexus phone of all time. Still inexpensive, still well-equipped, and sold direct by Google in even more countries. But the Nexus 5 reviewed less-than-favorably compared to more expensive high-end rivals, and it appears the phone never had a proper successor lined up.

While a good phone, the Nexus 6 was, in retrospect, a bit confusing as a Nexus.

In 2014, Android Silver was slated to launch - Google's attempt to commercialize stock Android as a selling point, in partnership with other phone OEMs. It was ambitious, to say the least. Instead of competing with other handset makers, Google would pick five phones at any one time that it would market in cooperation with wireless carriers in the US (to start) as being "silver edition" devices. They'd run stock Android, get updates direct from Google for a guaranteed period, have a direct line to Google support (a la Amazon's Mayday), a warranty and lost phone features, and there was even a whole on-boarding thing Google wanted to happen in terms of training carrier store employees on how to transfer people's information to their new phone and show them how to use it and various Google services.

It completely failed to materialize. The Nexus 6 was likely meant to be Silver's launch partner device - we'd heard it'd be called the Moto S - and this plan was scuttled when Silver died, and the Moto S rebranded to the Nexus 6. The problem is that the Nexus 6 wasn't much of a follow-up to the formula Google created with previous Nexuses. It wasn't cheap, it wasn't a mass-market screen size, and it didn't even sport a very distinct Nexus design language. It was really a Nexus in name and software only.

But with the 5X and 6P late last year, Google reaffirmed its commitment to the model it had established with the Nexus 4 and 5, and it doubled down on that model by launching two devices at deliberately tiered price points and screen sizes. The no-compromise Nexus 6P undercut flagship competitors easily, and is still probably the overall best-value Android device out there right now, especially if you can get one at even a minor discount. With Project Fi, Nexus Protect, Google Now Launcher, Google Camera, and a host of other apps and features, the Nexus puzzle is starting to come together in ways we only dreamed of five years ago.

The Hour Of Nexus

Remember all that business about smartphone hardware innovation slowing down? Here's the nice thing about that: it's making it easier and cheaper to build a smartphone that, in most respects, is competitive with that of your rivals. Might it be as nicely built? Not necessarily. Or have every single camera feature? Maybe not. But if you can market it for half the price of the best-selling phone's MSRP while maintaining 90% of the qualitative value versus that competitor, you've already got the right recipe. It's just about getting people to come taste the end product.

Slowing hardware innovation also means competitors are having a harder time differentiating (see: G5), and many will likely start to resort to gimmicks and general strangeness in an attempt to stand out from the crowd. None of them, though, can truly afford to let go of Google's services at this point - meaning none of them can get into the guts of Android in quite the way Google can. Now, Google has already offloaded a great deal of its software innovation to various apps and Google Play Services, but there's still a tremendous amount of control they can exert that no one else can. They can also offer a level of hardware and software integration in Nexus devices that they could never achieve with standard Android partners, because they're the ones driving that integration from both ends, as opposed to relying on a third party trying to make a business case. And, sure, they make all of this stuff available as part of Android itself, but no one is holding manufacturers' feet to the coals on actually implementing things like Sensor Hub, introduced on the Nexus 5X and 6P.

The Nexus 6P, doing a surprisingly good imitation of A Normal Phone You Actually Want To Buy

Though the Nexus 5X and 6P aren't perfect (particularly the 5X), they're still the best Nexus phones we've ever had. Many critics outright declared the Nexus 6P the best Android phone ever when it launched - I don't think any previous Nexus came remotely close to such a consensus. And in the US, those phones can even be bought without having to deal with a traditional carrier, assuming you're a single-line subscriber (Project Fi has no multiline incentives, and it shows, badly). You can even finance the phone, removing a major barrier for many consumers who don't want to spend $300 or $500 on a device outright. You get a warranty option, too!

The pieces are there - finally - for Nexus to be a major force here in the US phone market. (Abroad, I can't really assess as well.) And with smartphone manufacturers having ever-more trouble making a profit and adequately differentiating from their competitors, Google's strengths in Nexus - not being tied to the company's core profitability, and having direct control over Android itself - are more relevant than ever.

I greatly look forward to what's next for the Nexus phone program, because I have a feeling Google is well-aware that the tide is turning in its favor of late. In the grand scheme of things, there's precious little separating a Nexus 6P from a Galaxy S7 edge - far less than separated the Nexus 4 and the Galaxy S4, in my opinion - and Google seems to be inching ever-closer to the optimal Nexus formula with each passing year (barring the Nexus 6 / Silver misstep). The fact that the Nexus 6P garnered the most mainstream acceptance of any Nexus phone to date is, I feel, no coincidence. Google is getting dangerously close to the point where Nexus might start ruffling the feathers of its partners.

I can't say I'd mind.

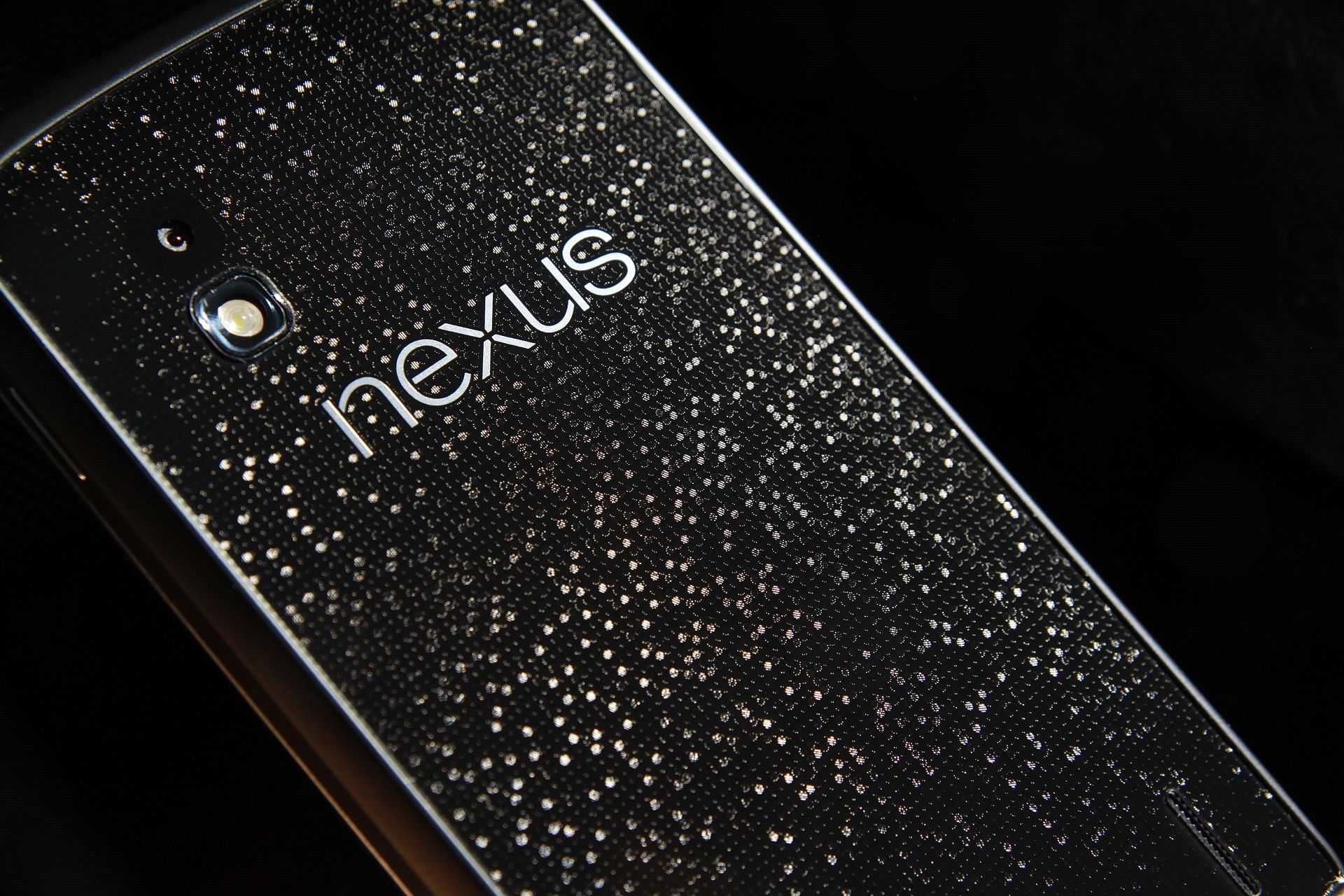

Lead image by Arek Olek - CC BY-SA 2.0