Today, Google announced that its acquisition of Motorola Mobility had officially closed. Make no mistake, this merger is something of a shotgun arrangement - and the offspring conceived out of wedlock is Android. So, how did we get here, two and a half years after the first DROID?

A Brief History Of Motorola And Android

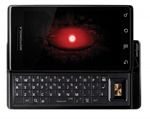

Motorola was once Google's model manufacturer partner. At least in the US, it produced what was the most popular "first generation" Android smartphone, the original Motorola DROID. The OG DROID was responsible for "hooking" many people on the operating system, whether through endlessly modifying and tweaking the device, or simply for its stellar build quality and reliability (those things were little tanks), it was truly the work-horse that first brought Android into the hands of a large number of people here in the US.

[EMBED_YT]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZISvhPeY9NA

[/EMBED_YT]

By the end of 2010, HTC had begun to outpace Moto in total device sales, though the company held on to the second place spot in the share of Android device manufacturers in the US until 2011, when Samsung muscled its way to top of the charts. Devices like the EVO 4G and Samsung's Galaxy S quickly took a chunk out of Motorola. Even the preemptive full-touchscreen strike that was the DROID X, and most phones thereafter, couldn't seem to propel Motorola back to the top.

After commercial and critical flops like the DROID X2, BIONIC, ATRIX, and a number of would-be BlackBerry candybar keyboard phones, Motorola's situation went from bad to worse. It seemed Moto just couldn't keep up. Huge community outcries against its device-locking policies haven't helped the company's image among enthusiasts, either, and its decision not to update two of its more recent handsets to Ice Cream Sandwich has owners in a furor. Regardless of the validity of these grievances, one thing is clear - Motorola Mobility, if not for Google sweeping in, probably wasn't on track to make a revolutionary turnaround.

While the RAZR and RAZR MAXX have proven to be much more successful devices in terms of garnering critical acclaim for the company, they seemingly haven't helped it compete against its primary foes - Motorola is down to a mere 10% of the smartphone market in the US. Here's the current smartphone sales picture in America (Q1 2012):

Source: NDP

For Q1 2012, Motorola managed to boost its smartphone sales year over year by 25%, to 5.1 million handsets, most of them sold in the US and China. Obviously, this hasn't been enough to keep up with the Joneses. Samsung, especially, has seen massive growth in the past year. But let's rewind for a moment.

The Buyout: Sophie's Choice

When Google announced its acquisition of Motorola back in August, some people (rightly) asked the big question: "Why?" The company certainly wasn't doing well (and has only lost market share since), and Google seemingly had it good letting its various manufacturer partners vie for market share, resulting in an Android-dominated smartphone ecosystem.

Then, it came out that things were, well, complicated. Patents were one of the major concerns Google actually expressed after the purchase - Larry Page himself said that "anticompetitive" behavior from the likes of Microsoft and Apple necessitated purchasing MMI to protect Android against those who would seek to use Moto's IP against the platform. Prior to the acquisition, one of Moto's biggest shareholders was prodding the board into selling off the company's patent portfolio piecemeal to give the firm additional liquidity. Suddenly, hindsight!

Who would have bought these patents? Microsoft. RIM. Apple. Basically, anyone with an interest in using them against Google and its partners. Just like they did with the Nortel patents. In fact, Microsoft was apparently interested in just buying Motorola altogether.

But given Mr. Icahn's very public endorsement of Moto selling off its IP - why didn't Google just pursue that route? It did, but Motorola didn't want to play ball. Motorola would have gotten a raw deal selling off its patents to Google, and while it may have been able to assert immunity from infringing them (a corporate "lifetime," non-transferable license), the patents were worth more to Moto in an offensive capacity. There's some truth to this - settling big patent lawsuits depends on the ability of both parties to assert infringement, meaning both parties have to own patents they can sue on. If Moto sold off its portfolio, it'd be a sitting duck for the likes of Apple and Microsoft.

It might, then, have been the more intelligent choice in the mind of CEO Sanjay Jha to just tell Google "buy us, or we'll sell to someone else." Jha admitted to being open to the idea of producing Windows Phone hardware, but clearly wanted the company to have other options (read: Android) on the table. But given Motorola's increasingly poor fiscal performance, it's likely the company's major shareholders were starting to look at more drastic measures to counteract the downturn (or cash out), such as the aforementioned IP sale.

But this explanation takes only one dimension of the buyout into account - why would Google, rather than attempt to hash out an IP deal, or wait for Jha to be ousted, take on a multi-billion dollar company (one not making a profit, mind you) just to get its intellectual property?

Backdoor Dealings, Huawei, And Furniture

That's when the rumors that Google was planning to flip Motorola's hardware business to Huawei started - a move that, as Forbes pointed out, sounds "logical." And logical it is - Google has never run a hardware company (though it does build some its own networking equipment), hell, it doesn't even really have any experience "selling" anything to consumers.

Considering Motorola's active presence in China, and Huawei's desire to have a larger US footprint, such a deal would make perfect sense. Of course, the federal government might have something to say about that - it has been notoriously suspicious of the Chinese firm, and basically prevented it from engaging in network hardware contracts in the US out of security concerns. Australia outright banned Huawei from bidding on a major network project in the country.

It seems unlikely that the FTC would be able to ignore the political pressure associated with a large, state-supported (Huawei receives loans with no or almost no interest from the Chinese government) Chinese corporation attempting to buy an iconic American brand. While logical, the idea of Google getting such a deal through regulatory hurdles seems almost insurmountable, if not a case of explicit bad faith in its purchase of Moto in the first place. It's also just not going to happen, based on new information - Google is making moves, restructuring Moto's management and products in big ways. There's no reason at this point to think Google isn't in this for the long play.

So, did Google really do it just for the patents? That's a bit like buying a foreclosed estate for the antique furniture and jewelry inside. Is it valuable, even unique? Sure. Is it worth buying real estate just to get your hands on it? Probably not. Does that mean this deal was cold, calculating, and well-thought-out, then? Not necessarily. In fact, the story of the deal's conception makes it sound like a reactive impulse-buy. It took Google and Motorola five days to hash out the terms, and the deal was conducted at the behest of Andy Rubin (after Google lost out on the Nortel patents), by Larry Page and Sanjay Jha personally. Rubin's first suggestion, apparently, was simply to buy Moto's patents, but Jha said no, and convinced Page to go for the "whole kit and kaboodle." Clearly, bigger things were afoot.

When Motorola Gives You Lemons...

Motorola Mobility is a major corporation - with over 20,000 employees working in 92 large facilities (and many smaller ones) in 97 countries. That kind of capital investment doesn't go away overnight, and it doesn't stop costing money just because Andy Rubin doesn't care about it. "Firewall" or not, Google has to do something with Motorola's hardware business, and it's going to have to get its hands dirty doing it. Right now, Motorola isn't turning a profit - and that must scare the bejesus out of Google's investors. The company may be generating well over $10 billion in revenue a year, but the bigger they are, the harder they fall - a sudden downturn in Moto's numbers could become a major financial liability for Google.

To say this $12 billion decision was a quick and dirty IP protection scheme does a disservice to the fact that Larry Page has shown he has big ideas for Google - ones that he isn't afraid to put in motion. To say that IP was anything but the reason the deal was put into motion in the first place is naïve; clearly, that's how this all got started. Google needed, or really wanted, those patents - but buying the whole of Motorola Mobility presented a new and interesting option for the company, and probably at a bargain-basement price, considering the separate value of the IP already at stake, as well as Motorola's financial state.

No doubt, Andy Rubin is the big cheese when it comes to all things Android development-related at Google, but by no means is he the man with the last word on all decisions related to it. Larry Page has made it very clear he's willing to kick ass and take names to keep Google relevant - often whether people seem to like it or not. Google+ is the most aggressively pushed product in the company's history - Google seems to almost flat out ignore the complaints of users that say the service has become too difficult to separate from products like Gmail and Search.

The acquisition of Motorola is yet another radical move by the new CEO, and it would be silly to believe that Page made the decision merely because of Rubin's growing concern over patents. And yet, that seems to be what so many people were suggesting, at least until Google spoke up in the past week.

While Page's statement on the importance of "anticompetitive" behavior from Apple and Microsoft, and therefore of the IP portfolio it acquired as part of the deal, would have supported such a conclusion, almost everything else we've heard to date does not. Page himself said at a town-hall meeting with Moto employees last year basically the exact opposite:

“It’s actually easier to make tremendous progress sometimes the more ambitious you are ... If you’re trying to do something kind of incremental, like a little bit similar to what you did before, it’s actually hard to get people excited about it.”

In other words: prepare for changes. Big ones.

Big Plans

What comes next? Trimming the fat, obviously. Google has a reputation for cutting down on workforces in its acquisitions - such as it did with AdMob, when it laid off about 8% of the company's employees. Compared to Motorola, AdMob was tiny. Motorola has active businesses in broadband modems, set top boxes, smartphones, dumbphones, and tablets. Some of these divisions can probably be reduced in size significantly, if not sold off entirely.

Well over half of the company's sales revenue is tied to its phone business, with the second-largest chunk going to set-top boxes. Smartphones now make up nearly 60% of all the company's handset sales. Google would do well to spin off the modem business to Cisco or Netgear, along with any patents related to the division. The set top box and dumbphone sectors are equally appealing targets for a little corporate austerity, but those might come into play later.

But the big picture plan? Getting Moto's ass in gear and putting out some awesome hardware. Eric Schmidt has put Google employee and former head of DARPA Regina Dugan in charge of a brand-new R&D unit at Motorola called the "Advanced Technology and Projects Group" (ATAP), with a focus on getting new, cool tech into phones fast. Says Dugan, "We are going to build a small, lean, Skunkworks-like group that is not afraid of failure." It's this kind of attitude that makes me love the idea of Google taking over a traditional corporation - they aren't afraid to break stuff.

Google has already put a new CEO in place (Dennis Woodside), and he's axed more than half of Moto's board in preparation for the switch. Woodside has made it clear his job isn't to sit idly by, it's to start moving things around - "My job is to make Motorola as successful as possible and deliver innovative hardware as a licensee of Android." He's also committed to cutting down on Motorola's expansive product portfolio, something sorely needed in its smartphone division.

Many took Andy Rubin's comments that Google would keep Moto "at arm's length" to mean from the whole of Google. In fact, Rubin was talking about the Android team. This is kind of a "duh" decision - Google does not want to alienate major allies like Samsung and HTC by providing Motorola preferential access and attention when it comes to Android. And it won't - approvals of the deal in the US, Europe, and China rely on it.

Andy Rubin has historically wanted Google to take as "hands-off" an approach with Android licensees as possible, and focused heavily on device activation figures as compared to the quality of Android-powered products (we're also talking about someone who didn't think the Market was all that "important"). Rubin actually said the following at MWC in February:

It would be “completely insane” to try to turn Motorola, which currently has “single-digit” market share in Android mobile handsets, into the dominant player. “It just isn’t going to happen,” he said, adding that “the way Android’s going to continue to be successful is to be neutral.”

Something tells me Larry Page has other ideas about how this acquisition is going to play out. This isn't Andy Rubin's project, though, and his "firewall" comment has made that clear - he has and will have nothing to do with Motorola for the foreseeable future. Just because Motorola can't work with the Android team directly doesn't mean Google isn't going to make sure Motorola puts out the best damn Android phones it can. And make no mistake - Google is now directly competing with its licensing partners Samsung, HTC, and LG, despite whatever Andy Rubin might say about "neutrality."

This isn't some fleeting marriage based on patents - it's an attempt to change the game.